Introduction to CUDA

Overview

Teaching: 30 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

What is CUDA and how is it used for computing?

What is the basic programming model used by CUDA?

How are CUDA programs structured?

What is the difference between host memory and device memory in a CUDA program?

Objectives

Learn how CUDA programs are structured to make efficient use of GPUs.

Learn how memory must be taken into consideration when writing CUDA programs.

Introduction to CUDA

In November 2006, NVIDIA introduced CUDA, which originally stood for “Compute Unified Device Architecture”, a general purpose parallel computing platform and programming model that leverages the parallel compute engine in NVIDIA GPUs to solve many complex computational problems in a more efficient way than on a CPU.

The CUDA parallel programming model has three key abstractions at its core:

- a hierarchy of thread groups

- shared memories

- barrier synchronization

There are exposed to the programmer as a minimal set of language extensions.

In parallel programming, granularity means the amount of computation in relation to communication (or transfer) of data. Fine-grained parallelism means individual tasks are relatively small in terms of code size and execution time. The data is transferred among processors frequently in amounts of one or a few memory words. Coarse-grained is the opposite in that data is communicated infrequently, after larger amounts of computation.

The CUDA abstractions provide fine-grained data parallelism and thread parallelism, nested within coarse-grained data parallelism and task parallelism. They guide the programmer to partition the problem into coarse sub-problems that can be solved independently in parallel by blocks of threads, and each sub-problem into finer pieces that can be solved cooperatively in parallel by all threads within the block.

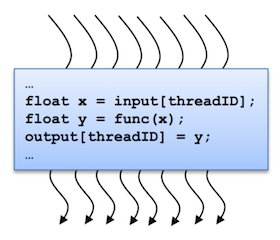

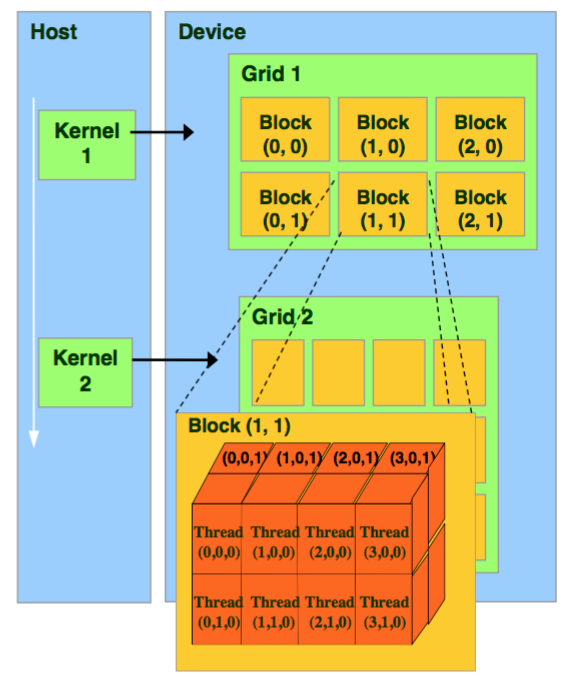

A kernel is executed in parallel by an array of threads:

- All threads run the same code.

- Each thread has an ID that it uses to compute memory addresses and make control decisions.

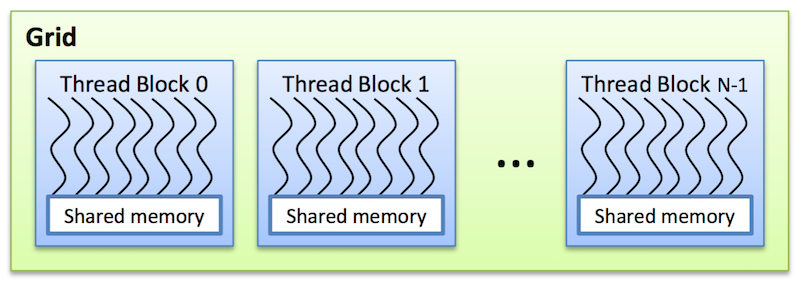

Threads are arranged as a grid of thread blocks:

- Different kernels can have different grid/block configuration

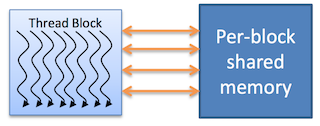

- Threads from the same block have access to a shared memory and their execution can be synchronized

Thread blocks are required to execute independently: It must be possible to execute them in any order, in parallel or in series. This independence r equirement allows thread blocks to be scheduled in any order across any number of cores, enabling programmers to write code that scales with the number of cores. Threads within a block can cooperate by sharing data through some shared memory and by synchronizing their execution to coordinate memory accesses.

The grid of blocks and the thread blocks can be 1, 2, or 3-dimensional.

The CUDA architecture is built around a scalable array of multithreaded Streaming Multiprocessors (SMs) as shown below. Each SM has a set of execution units, a set of registers and a chunk of shared memory.

In an NVIDIA GPU, the basic unit of execution is the warp. A warp is a collection of threads, 32 in current implementations, that are executed simultaneously by an SM. Multiple warps can be executed on an SM at once.

When a CUDA program on the host CPU invokes a kernel grid, the blocks of the grid are enumerated and distributed to SMs with available execution capacity. The threads of a thread block execute concurrently on one SM, and multiple thread blocks can execute concurrently on one SM. As thread blocks terminate, new blocks are launched on the vacated SMs.

The mapping between warps and thread blocks can affect the performance of the kernel. It is usually a good idea to keep the size of a thread block a multiple of 32 in order to avoid this as much as possible.

Thread Identity

The index of a thread and its thread ID relate to each other as follows:

- For a 1-dimensional block, the thread index and thread ID are the same

- For a 2-dimensional block, the thread index (x,y) has thread ID=x+yDx, for block size (Dx,Dy)

- For a 3-dimensional block, the thread index (x,y,x) has thread ID=x+yDx+zDxDy, for block size (Dx,Dy,Dz)

When a kernel is started, the number of blocks per grid and the number of threads per block are fixed (gridDim and blockDim). CUDA makes

four pieces of information available to each thread:

- The thread index (

threadIdx) - The block index (

blockIdx) - The size and shape of a block (

blockDim) - The size and shape of a grid (

gridDim)

Typically, each thread in a kernel will compute one element of an array. There is a common pattern to do this that most CUDA programs use are shown below.

For a 1-dimensional grid:

tx = cuda.threadIdx.x

bx = cuda.blockIdx.x

bw = cuda.blockDim.x

i = tx + bx * bw

array[i] = compute(i)

For a 2-dimensional grid:

tx = cuda.threadIdx.x

ty = cuda.threadIdx.y

bx = cuda.blockIdx.x

by = cuda.blockIdx.y

bw = cuda.blockDim.x

bh = cuda.blockDim.y

x = tx + bx * bw

y = ty + by * bh

array[x, y] = compute(x, y)

Memory Hierarchy

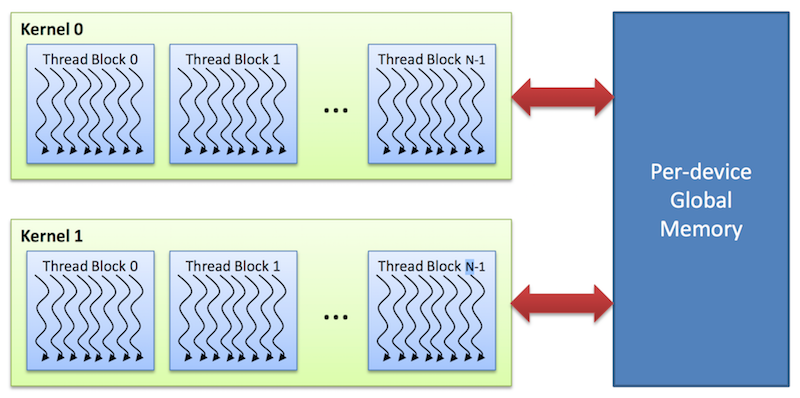

The CPU and GPU have separate memory spaces. This means that data that is processed by the GPU must be moved from the CPU to the GPU before the computation starts, and the results of the computation must be moved back to the CPU once processing has completed.

Global memory

This memory is accessible to all threads as well as the host (CPU).

- Global memory is allocated and deallocated by the host

- Used to initialize the data that the GPU will work on

Shared memory

Each thread block has its own shared memory

- Accessible only by threads within the block

- Much faster than local or global memory

- Requires special handling to get maximum performance

- Only exists for the lifetime of the block

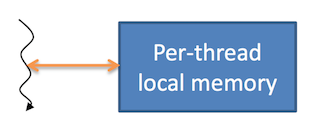

Local memory

Each thread has its own private local memory

- Only exists for the lifetime of the thread

- Generally handled automatically by the compiler

Constant and texture memory

These are read-only memory spaces accessible by all threads.

- Constant memory is used to cache values that are shared by all functional units

- Texture memory is optimized for texturing operations provided by the hardware

CUDA Foundations: Memory allocation, data transfer, kernels and thread management

There are four basic concepts that are always present when programming GPUs with CUDA: Allocating and deallocating memory on the device. Copying data from host memory to device memory and back to host memory, writing functions that operate inside the GPU and managing a multilevel hierarchy of threads capable of describing the operation of thousands of threads working on the GPU.

In this lesson we will discuss those four concepts so you are ready to write basic CUDA programs. Programming GPUs is much more than just those concepts, performance considerations and the ability to properly debug codes are the real challenge when programming GPUs. It is particularly hard to debug well hiding bugs among thousands of concurrent threads, the challenge is significantly harder than with a serial code where a printf here and there will capture the issue. We will not discuss performance and debugging here, just the general structure of a CUDA based code.

Memory allocation

GPU cards are usually come as a hardware card using the PCI express card or NVLink high-speed GPU interconnect bridge. Cards include their own dynamic random memory access memory (DRAM). To operate with GPUs you need to allocate the memory on the device, as the RAM on the node is not directly addressable by the GPU. So one of the first steps in programming GPUs involve the allocation and deallocation of memory on the GPU.

The memory we are referring here in the GPU is called “Global Memory”, it is the equivalent to the RAM on a computer. There are other levels of memory inside a GPU but in most cases we talk about the “Global memory” as “device memory” with those two expressions being used interchangeable for the purposes of this discussion.

Allocating and deallocation of memory on the device is done with cudaMalloc and cudaFree calls as shown here:

float *d_A;

int size=n*sizeof(float);

cudaMalloc((void**)&d_A, size)

...

...

cudaFree(d_A);

It is customary in CUDA programming to clearly identifying which variables are allocated on the device and which ones are allocated on the host. The variable d_A is a pointer, meaning that its contents is a memory location. The variable itself is located in host memory but it will point to a memory location on the device, that is the reason for the prefix d_.

The next line computes the number of bytes that will be allocated on de device for d_A. It is always better to use floats instead of double if the need for the extra precision is not a must. In general on a GPU you get perform at least twice as fast with single precision compared with double and memory in the GPU is a precious asset compared with host memory.

Finally to free memory on the device the function is cudaFree. cudaMalloc and cudaFree look very similar to the traditional Malloc and Free that C developer are used to operate. The similarity is on purpose to facilitate moving into GPU programming with minimal effort for C developers.

Moving data from host to device and back to host

As memory on the device is a separate entity from the memory than the CPU can see, we need functions to move data from the host memory (RAM) into the GPU card “Global memory” (device memory) as well as from device memory back to host.

The function to do that is cudaMemcpy and the final argument of the function defines the direction of the copy:

cudaMemcpy(d_A, A, size, cudaMemcpyHostTodevice)

...

...

cudaMemcpy(d_A, A, size, cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost)

Kernel functions

A kernel function declares the operations that will take place inside the device. The same code on the kernel function will run over every thread span during execution. There are identifiers for the threads that will be used to redirect the computation into different directions at runtime, but the code on each thread is indeed the same.

One example of a kernel function is this:

__global__ simple_kernel(float* A, int n)

{

int i = blockDim.x * blockIdx.x + threadIdx.x;

A[i]=1000*blockIdx.x+threadIdx.x;

}

Example (SAXPY)

#include <stdio.h>

__global__

void saxpy(int n, float a, float *x, float *y)

{

int i = blockIdx.x*blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (i < n) y[i] = a*x[i] + y[i];

}

int main(void)

{

int N = 1<<20;

float *x, *y, *d_x, *d_y;

x = (float*)malloc(N*sizeof(float));

y = (float*)malloc(N*sizeof(float));

cudaMalloc(&d_x, N*sizeof(float));

cudaMalloc(&d_y, N*sizeof(float));

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

x[i] = 1.0f;

y[i] = 2.0f;

}

cudaMemcpy(d_x, x, N*sizeof(float), cudaMemcpyHostToDevice);

cudaMemcpy(d_y, y, N*sizeof(float), cudaMemcpyHostToDevice);

// Perform SAXPY on 1M elements

saxpy<<<(N+255)/256, 256>>>(N, 2.0f, d_x, d_y);

cudaMemcpy(y, d_y, N*sizeof(float), cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost);

float maxError = 0.0f;

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++)

maxError = max(maxError, abs(y[i]-4.0f));

printf("Max error: %f\n", maxError);

cudaFree(d_x);

cudaFree(d_y);

free(x);

free(y);

}

Key Points

CUDA is designed for a specific GPU architecture, namely NVIDIA’s Streaming Multiprocessors.

CUDA has many programming operations that are common to other parallel programming paradigms.

Careful use of data movement is extremely important to obtaining good performance from CUDA programs.